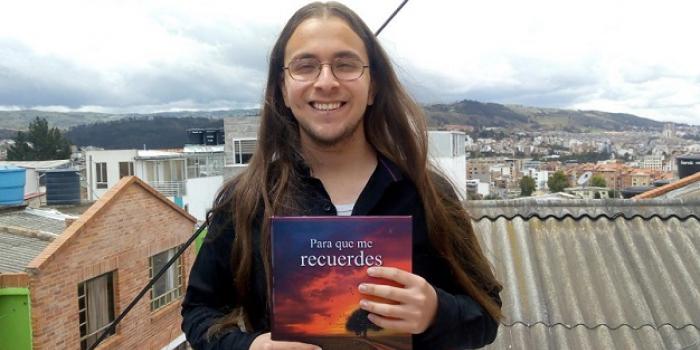

Jesús Santiago Ardila, literature as resistance

Victim of several displacements, and still without graduating from university, he has written two books that not only expose his passion for the story, poetry and the novel, but also the ideal of leaving his trace in the conscience of society.

By Erick González G.

He is young, only 20 years old. His short life itinerante and his family resemble a blues road movie, where each season brings its sadness along the way. Jesús Santiago Ardila the protagonist of these lines knows it. And he knows that a jam session is the most appropriate soundtrack for his biopic or biographical film, not because of the pleasure that characterizes this type of musical improvisation, but because violence imposes its sinister rhythm, and although there are drills for earthquakes, nobody rehearses for a displacement.

And that, Jesús Santiago Ardila knows very well. From the age of five, when his first displacement occurred, he could count on an abacus his changes and pains, but not sufferings, because the pain is temporary and, in these cases of plunder, shared, but the suffering is persistent, according to the onslaught in the soul, and in his, the music and the lyrics mediated to shield it.

The inxil

Due to his smallness at that time, Jesús Santiago zaps in his memories to tune into November 2004 when he endured his first inxilio or internal displacement in a Hamlet of Brussels rural district, in the municipality of Pitalito, in the department of Huila. "My father received threats from a guerrilla group, and my mother had a bad feeling after they tried to assassinate him on his farm, where they wounded one of his workers and killed the mule and the dog, so we went to Neiva".

Days before his father had sent his eldest son to Antioquia, as an antidote to his imminent forced recruitment, and thus prevented him from being the fifth young man in the sad census, of the Single Victims Registry, of boys, girls and adolescents linked to armed groups in Pitalito and its villages and townships.

Displacements (10.115), homicides (3.834), threats (1.056) and forced disappearances (278) are some of the victimizing events that this region has endured and that with 14.119 victims make Pitalito the third municipality with the most people affected by the conflict armed in Huila, after Neiva (21.880) and Algeciras (18.657).

Years later, Jesús Santiago would write in his first book Para que me recuerdes (For You To Remember Me): "There is a desperate cry in the world for the world itself, which could be appeased, perhaps, with a little illusion ...". That cry and cry out for themselves –for eviction and protection– did not subside in Neiva, despite the illusion, and perhaps that is why in the phrase of his debut opera he wrote down the adverb perhaps, due to the utopia of his wishes. “We don't feel safe there. My brothers stayed in one place and my parents in another, but they realized that there were people like that hanging around, so we went to Bogotá”.

For a year they were 2.600 meters closer to the stars. But "people like that" kept hanging around. One day his father decided to house a blind man with his wife in his house, driven by his Achilles heel: kindness and feelings of justice and solidarity that, according to Jesús Santiago, his father has always professed towards the needy, without realize that they were the true blind, as they did not intuit, as the days passed, that their tenant saw no opportunity to gather information about them to send it to their pursuers, with the intention of putting them three meters closer to the center of the Earth.

Some neighbors alerted them to this emissary, to his grave intention and his false blindness, so they applied the same law to him. They turned a blind eye while they were looking for a destination and sooner they disappeared. Between prayers and fate, an architect appeared to them, who offered his father a job as administrator of a farm in Boyacá.

"When life takes a break, it allows us to give ourselves one in which it enters through our lungs and walks through the arteries," Jesús Santiago would also write in “Para que me recuerdes”.

In the Suaquira hamlet, in the municipality of Pachavita, with their pigs, cows and trees, they were able to enjoy some tranquility. There she studied in a rural school, in a classroom that accommodated all primary grades. “I had to walk an hour and a half to get there, along a path bordered by a river for most of the way. And always one of my parents accompanied me on the trips”.

That intermission lasted seven months. Now the exodus was due to scarcity and that shortage established the route: to Pachavita, where the older brother arrived; to Simijaca square, where they subsisted selling meat pies; to Maní, in Casanare, to sell clothes and work in construction, and to Orocué, on the border with the department of Meta, where the promise of profits from the sale of fish put them on the hook.

"They didn't do well with the fish, so my dad started working in construction, but he cut off two of his fingers, so he decided to sell clothes on the street in a cart".

That wagon became the down payment of his faith and, in time, a house of two plants with business included. Orocué had become an oasis after so much mirage.

The awakening of art

Primary school was passing, when at the age of nine a teacher tempted the child Jesus with a flute, an instrument that was the baptismal font for his new creed: art.

And if the flute was his baptism, the clarinet would be his first communion. "Thanks to the clarinet I got to know Casanare, Meta and Vichada", memories that probably pass through its verse: "I went through each part of the melody with the little will that I can have and then threw up until the last note”.

In eighth grade he had another revelation. The reviews and essays that his Spanish teacher required for homework presented him with another art: literature, and he married that art.

With the tasks, he learned to file imperfections, and the discovery of Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, Mario Benedetti, Fernando Soto Aparicio, Rafel Ortiz González and José Eustasio Rivera ignited that maelstrom for writing. "When I got to the University I kept writing and in the first semester I gave poems to pedestrians on the street."

But the seven years of fat cows at Orocué would end before that college experience. “My father began to have threats for helping the population victims of the conflict; They told him: 'I know where you lives, if you don't go we'll kill you”.

Again the inxilio, the fourth, now destined for Arauca, and again from the epicenter of prosperity to the suburbs of life, but the desire to study exempted Jesús Santiago from that experience. He remained in Orocué, at the home of his older brother and his wife –the other house was lost–, ignorant of the new living conditions of his family. Not only did he earn his bread with his clarinet sweat, he was able to save for college tuition, although he had to hold a raffle to complete the dream.

In 2016, he entered a career in Economics at Universidad Pedagogica y Tecnologica de Colombia (UPTC), in Tunja, a choice that would seem to go against the grain of his artistic inclinations, but actually choose a career more akin to his rapture. literary was a matter of economics.

During the Easter holidays of that year, he traveled to Arauca, where melancholy assailed him when he saw the narrowness in which his loved ones survived. “That was the worst episode in my family's history. My parents, my middle brother, my ex-sister-in-law and a nephew lived in a house built of plastic, on a dirt floor, in an invasion”.

The images of his parents' searching, especially his mother's gesture when all the food she had prepared to sell on the street fell to the pavement, he carries them in his soul. "Those memories sprout, take root and change with the mental seasons", expresses Jesús Santiago with the resignation of someone who still believes himself to be besieged by life.

Despite his feeling of responsibility, he returned to classes, and at the end of his semester his father advised him to go to the Repair Fund for Access, Permanence and Graduation in Higher Education aimed at the Victims of Armed Conflict, an agreement between the Icetex and the Victims Unit, to which he applied and for which he is already in the ninth semester.

He has lived not only in economics. That shyness that he confesses that makes him prefer the solitude of his room, perhaps in the manner of an insilian - that kind of voluntary ostracism within himself, because of the social and economic order, allowed to forge itself from literature and music, from the blues of Robert Johnson and Gary BB Coleman, from the jazz of Chet Baker, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Billy Holliday and, of course, the clarinetist Benny Goodman, the bolero trio Los Panchos, rock and metal.

Leaving trace

"There are silences of silences, where appreciation, misfortune, happiness, sympathy, benevolence or well-being are hidden", he wrote. And from that silence, his first book Para que me recuerdes arose at the beginning of this year, which reveals his taste for poetry, short stories and short novels. "It began as a project of dialogue with someone very important, full of errors, flaws", a confession that shows an attitude: being a writer in sight.

His insilio has also been inhabited by his parents since he saw them in Arauca, despite the fact that a year later an aunt sent them the money to move to the department of Antioquia, to the town where they fell in love. A couple of weeks ago his father was forced to move, again to help those in need, and he survives thanks, again, to a bad feeling from his wife.

The visa to get out of these concerns is his girlfriend, a young woman on the scale of his desires: a philosopher, akin to the thoughts of the sages of classical Greece, Heidegger and, especially, the concepts of Hannah Arendt, about whom he prepares a written based on his views on himto freedom.

And that freedom so lashed out in our days and so harassed in his life, Jesús Santiago found it in some Latin American authors of the twentieth century who join their banner for a more humane and equitable society. “That way they raised their voices in defense of the homeless helped me to draw up certain purposes regarding writing; I think that ultimately it is his way of changing the world, even if it is a naive vision”.

From his experience, he understands that “he could not separate art from politics, because giving an expression involves others adapting it to their susceptibility, and if that expression has to do with what a group of people is experiencing at a certain moment, it would be a approach to the beautiful from the human”.

In his words, something can be seen in him of that literary resistance raised by the great French poet René Char, who wrote: "I do violence to myself to preserve, despite my humor, my ink voice", in The Leaves of Hypnos, everything a proclamation against human irrationality, written as a kind of bulwark against the Nazi occupation. It seems that towards this north he has directed his second book, a kind of alter ego, in which he poses many expectations, because he knows that despite his concerns “he makes his way by walking”, as Antonio Machado said, but he knows that the most important thing It is not in the footprint - the where or the how - but in the footprint.